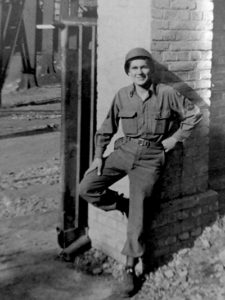

Cpl. William Beckman, right, perhaps with his squad after a football scrimmage.

July 2, 1944: an American soldier slowly walks the steep incline to board a ship for an extended voyage overseas. All around him the city of New York is alive with the hustle and bustle of everyday life.

Kids run around the boardwalk chasing each other while the balloons wrapped around their wrists bobble and struggle to catch up. Young couples walk hand in hand as if they are the only two people on earth, unaware of large ships preparing to leave port.

In the distance, faint screams can be heard as the clicking chains of an old wooden roller coaster release their passengers down a rickety hill of twists and turns. The sun is shining, and the smells of hot dogs, sea salt and sweat blend to form a strange yet familiar fragrance.

Cpl. William Beckman, the author’s grandfather.

Just a year ago, William Beckman was 17, attending a Cincinnati Reds game with his father. Hot dog vendors, salt on the soft pretzels and sweat from a hot July summer in Ohio mirrored the aromas that were dancing all around him as if someone captured the moment in a bottle, removing the cork right under his nose.

As William looked up at the massive ship, his eyes caught a glimpse of her name, the RMS Scythia. It reminded him of the first time he saw the Carew Tower. Each tilt of his head continued to inch its way to the top of the immense steel structure until finally a full image came into view. The Scythia would be his home for the next 12 days as he and 4,000 soldiers sailed across the German U-boat-infested Atlantic Ocean to join other units already stationed on the beaches of Normandy. Just a month prior, D-Day propelled the United States and its allies into a fierce battle for the Western Front.

As William took his place on the deck of the Scythia, young, attractive nurses passed out chocolate candy bars for the long voyage. Placing the chocolate into his uniform pocket, he looked across the bay at the convoy of 40 ships preparing to leave port to provide support to troops already stationed in Europe. It was a hot summer day, but a slight breeze rippled across the sea of American flags hanging from the ships’ sterns as if to wave goodbye to their homeland. For many of these soldiers, this voyage was a one-way trip. Never again would they see their families or witness a baseball game, taste a crisp cold beer on a hot summer day or smell a hot dog roasting on a charcoal grill. For some it was a farewell; for others it was a funeral procession.

Like a massive beast quickly awakened from its winter’s sleep, the boilers of the Scythia fired up and released a thunderous roar across a lazy Sunday New York bay. Soon after, the other ships in the convoy ignited their engines and all at once bellowed out a battle cry across the Atlantic Ocean.

Cpl. Beckman, left, and two other soldiers during their WWII service.

Feeling a great sense of pride for his country, William placed his hand on his heart. In addition to a melted chocolate bar, he could feel his beating heart pounding heavily like a bass drum in a marching band. There was so much uncertainty that lay ahead in those choppy, unpredictable waters. German U-boats roamed the uncharted territory, like sharks waiting in the deep, dark silence to pick off their unsuspecting prey. Ships sailed in convoys for protection. If one ship fell behind, the rest of the convoy continued to its destination, leaving the lone vessel bobbing alone, vulnerable to the enemy. William felt a sense of hope and reassurance when he saw that the Scythia was leading the pack.

July 8 was very much like the previous five days at sea. There was little to do, and each day came and went the same as the last. Someone had managed to smuggle on a football. That helped pass the time until a hail-Mary attempt ended horribly after the ball was intercepted by the rough seas. William hoped his fate would be different than that old football kicking and fighting to stay afloat. As the crew began to prepare for another night on the ship, the Scythia moaned and groaned as if she, too, were tired and ready for the journey to be over.

Word began to spread like a match to a newspaper that the massive boilers powering the Scythia had stopped. With no power and nightfall approaching, the Scythia and its 4,000 passengers floated helplessly in a dark and desolate sea. One by one the other ships in the convoy approached and passed the distressed vessel. Their lights shined bright then faded into the dense night like a sparkler on the Fourth of July, quickly extinguished in a bucket of water.

As the last boat and lifeline passed, a thunderous roar could be heard coming from the Scythia. Her massive boilers had awakened, igniting a spark of hope throughout the ship. William and his crewmates had survived this ordeal, but their fate lurked ahead behind the hedgerows, dense forests and machine guns of German-occupied lands.

This is the third in a series of remembrances by Chris Beckman, a Cincinnati commercial lines underwriting manager, of his family members’ service in World War II. His grandfather, William Beckman, served in the United States Army, Technician Fifth Grade, Corporal (1943-1946). William Beckman’s cousin, Joe Beckman, served in the United States Army Air Corps (1941-1945).

You can read their stories here: